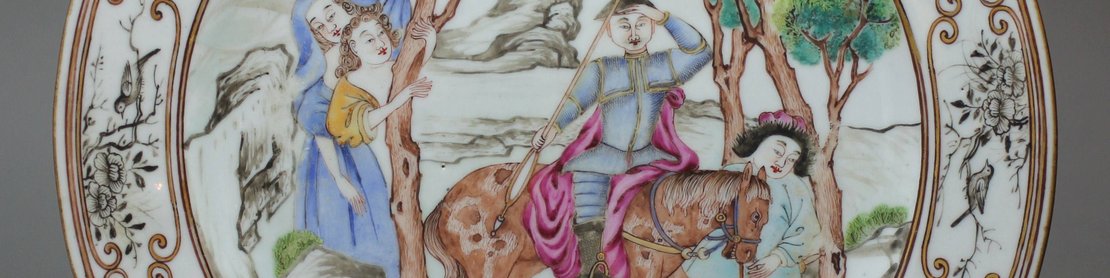

Chinese famille-rose porcelain refers to Chinese porcelain decorated with predominantly pink coloured enamel, made from colloidal gold, which was first used in the late Kangxi period. In early eighteenth century Chinese famille-rose was sometimes referred to as ‘fencai’ meaning foreign colour.

There are various theories as to how this enamel came to be used in China, one suggestion is that it was invented by Andreas Cassius of Leyden in the 17th century and found its way to China through the Jesuits, possibly by courtesy of Guiseppe Castiglione. However, I think it is more likely that the introduction of this enamel was the result of the Jesuits being aware of its use by European enamellers at Limoges or some of the German factories where the rose coloured enamel on copper had been in use prior to its discovery by Andreas Cassius. Possibly it was first used on Canton enamel.

In Qing famille-rose enamelled wares the glaze is different from that used for under-glaze blue. According to Pere d’Entrecolles the glaze was made more opaque by the addition of liquefied fern ash. The resulting glaze enhanced the effect of the coloured enamels. Peire d’Entrecolles also states that, in the case of Qing porcelain where the enamels were to be finely shaded, an additional enamelled coating was added to the glaze using a white powder composed of a type of quartz sand mixed with lead powder. This technique was used on cloisonné wares from Limoges. In the Guimet Museum in Paris there is a pair of famille-rose cups inscribed by the Jingdezhen potter with “I L” the mark for Jaques Laudin (1627-1695), a maker of cloisonné wares at Limoges.

On famille-rose porcelain made at Jingdezhen - this factory was restarted in 1683 after its destruction during the Qing defeat of the Ming earlier in the century - the enamel was not initially as clean and translucent as it quickly became in the Yongzheng period, when it reached its qualitative peak. There are one or two dateable early Canton enamel pieces where the enamel is quite poor. The fine and delicate decoration with fine shading to the enamels on Yongzheng porcelain had a feminine quality, unlike the famille-verte porcelain made in the preceding period of Kangxi, when the decoration tended to be very much stronger. In the subsequent Qianlong period the quality on the export wares started to deteriorate quite rapidly. The enamels became far less clean and translucent and the drawing not so fine. In the Imperial porcelain the quality remained much higher.

It is worth noting that like the famille-verte wares, famille-rose was much copied in nineteenth century Europe, particularly by Samson. The Samson copies at their best can be quite good. In genuine pieces, the enamels are usually much thicker than that found on most copie,s including those by Samson. It is also worth noting that the halo round the enamels is also a useful guide to the authenticity of a piece. Another characteristic of Samson is that its glaze is too clean and glassy and this can be best seen where it accumulates inside foot rims. Copies often got the potting wrong. During the Kangxi period the rims of bowls tended to be quite thin, whereas later on the rims were inclined to be thicker. The thickness and weight of the bases of 18th century bowls were nicely balanced to the rest of the dish or bowl, but in the 19th century most of the weight often resided in the base.

One of the finest groups of Yongzheng export porcelains are the ‘eggshell’ wares which sometimes have a ruby back. Unfortunately, these are well copied not only by Samson in France, but also in Hungary. The best way of detecting some of the good copies is by closely looking at the drawing which is somewhat stiff, particularly in the cartouches on the rim bands. For Imperial use, the best famille-rose is called Gu Yue Xuan where some of the motives were inspired by the Italian painter Castiglione. These again are

much copied. Most pieces are decorated with birds, flowers and rock-work and occasionally poems. On genuine pieces the flowers have lively spring-like quality whereas on the copies the flowers look in need of watering. The body of the genuine pieces is extremely white. Both the glaze and the body are primarily composed of petuntse fired together at a very high temperature giving them a gem-like quality. The very distinctive four character seal marks are written in over-glaze blue enamel (with the exception of a few produced in the Yongzheng period) which, on close examination, have an iridescent halo.

Large numbers of famille-rose services with family armorials were made for export to Europe, but the Kangxi and Yongzheng examples are somewhat rare.

Some of the best books for further reading are:

China for the West

David Howard and John Ayers

Published by Sotheby Park Bernet.