Ho no ōki oranda-bune ya kumo no mine

A Dutch ship

With many sails:

The billowing clouds.

Shiki, trans. Blyth

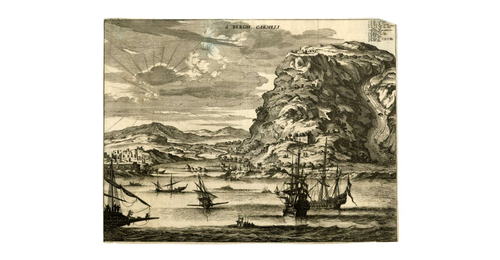

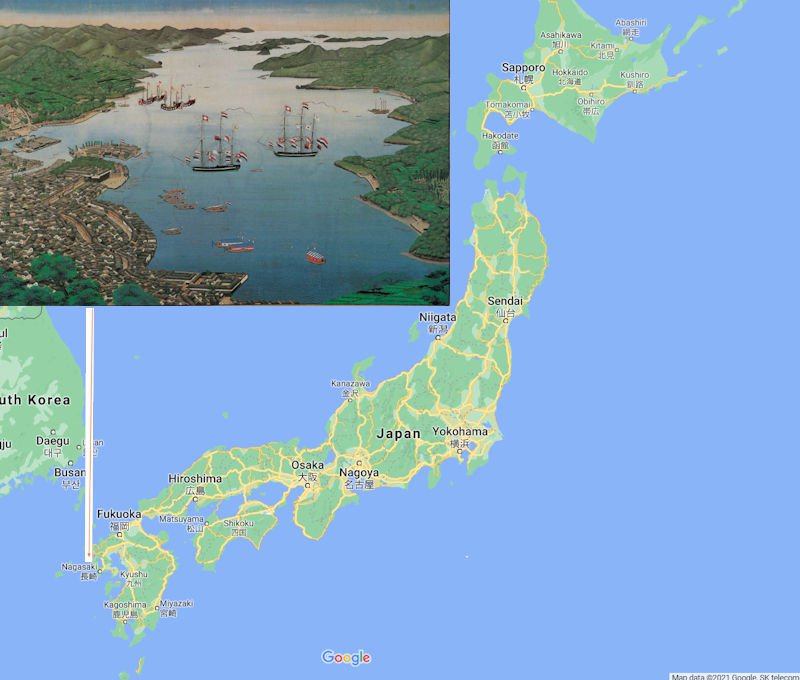

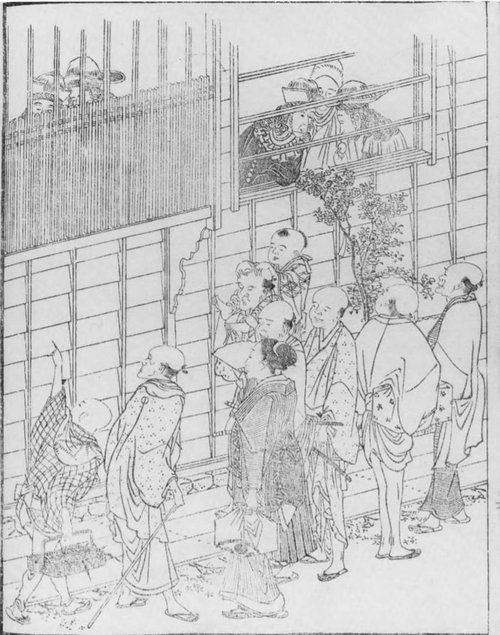

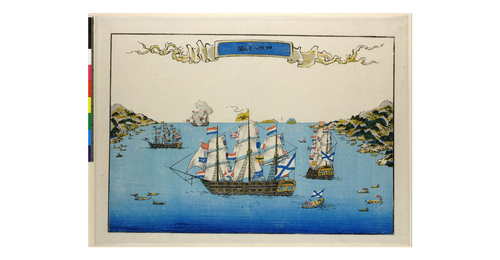

This teapot provokes a number of considerations on cultural and political levels. At the time of its production in the early eighteenth century, the sakoku (鎖国) policy of the Tokugawa had been in place for nearly a century. This meant that the only ships in living memory which had been allowed to trade at Deshima were Dutch and Chinese. Markedly different from the Chinese and Japanese vessels to which residents of Nagasaki were accustomed, large sea-faring European ships sparked great interest and were the subject of paintings and texts from the seventeenth century onwards (Screech, 2002 p.61). However curious locals may have been about the European traders with red hair (in popular culture the Dutch were referred to as kōmo, or ‘red-furred’), Tokugawa policy aimed to ensure minimal contact between Japanese and Europeans, and as such European traders were not generally permitted to leave the shores of Deshima. While under Japanese authority, crews in fact had to hand over the sails of their ships and could only leave when sanctioned to do so: had the design of this teapot been based on a Japanese observational drawing of Deshima rather than an imported European print, fewer billowing sails would perhaps be present.

Despite restrictions, points of contact were deemed necessary by the government, and Japanese caterers, interpreters, officials and sex workers were stationed on the island – all paid for by the VOC, which was also legally required to rent the land upon which it was permitted to trade. Alongside other requirements and restrictions, the Dutch were expected to undergo an annual visit to Edo to present the shogunate with gifts as a mark of subordination and respect. This practice reflects the policy of sankin kotai, which demanded that daimyo (regional lords) travelled to the capital every year with a retinue in accordance with the size and wealth of their domain in a show of military loyalty. The ‘splendid display’ of the processions both by local lords and Dutch parties alike were clearly arranged to demonstrate the command that the shogunate held over such political and commercial powers (Koshōken Furukawa, Toyuu Zakki in Plutschow, 2006 p.22).

Cooperation with such demands was in the best interests of the Dutch, as their privileged trading position in Japan and East Asia at large was enormously lucrative. The VOC (Vereenigde Oost Indische Compagnie) started as a spice trading organisation in the early seventeenth century, but over the course of the next hundred years expanded its operations to become a global company-state, controlling an entire interconnected global supply chain. It had a royal charter giving it a monopoly not only on trade but also on political dealings in new territories (Grenville, 2017; Boxer, 1979). Contemporary seventeenth-century records of Dutch exports (such as the Dagh-Registers of Batavia, Hirado and Deshima published in Volker, 1954) offer valuable data on volumes of ceramics traded, but do not account for private dealings (nunkei) conducted alongside official trade, meaning that exact figures cannot be known. In the rare instances of extant Japanese documents, comparison with the official Dutch figures reveal the extent of this illicit trade: the official VOC records for 1711 state that 9000 pieces of porcelain had been purchased, whereas according to the Japanese reports the figure was in fact 179,246 (Screech, p.12). Other studies of available figures indicate the wider picture of Dutch trade: an estimated 227,692 pieces were imported by the VOC into the Netherlands between 1660 and 1684, for example (Viallé, 2000 in Jorg, 2003 p.12), rising to tens of thousands of pieces a year in later decades. It is worth noting that despite these large volumes, the Dagh-Registers suggest that wares destined for European markets only made up 10% of the total ceramics exported (largely by the VOC) from Japan, and that the bulk of exports were in fact intended for Asian markets (Volker, 1954).

Interestingly, this teapot was produced at a time of recession in Japan, which drastically affected the whole country from the 1710s through to the 1730s (Impey 1973). Whereas previously there had been a healthy domestic demand for ceramic wares (Impey, Jorg & Mason, 2009 p.25), this economic decline alongside the introduction of sumptuary laws as part of the kyōhō reforms (kyōhō no kaikaku), likely resulted in a renewed focus at the porcelain kilns on the production of items such as this teapot, overtly designed and made for consumption overseas.

Bibliography/Further Reading

Boxer, C.R. 1979. Jan Compagnie in War and Peace, 1692-1799. A Short History of the Dutch East-India Company. Hong Kong: Heinemann

Grenville, Stephen. 2017. The First Global Supply Chain. Lowy Institute. Accessed 27.7.2021

Gunn, Geoffrey C. 2011. History Without Borders: The Making of an Asian World Region, 1000-1800. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press

Ho, Chuimei. 1994. ‘The Ceramic Trade in Asia, 1602-82’ in Latham, A.J.H. and Kawakatsu, Heita (eds.) Japanese Industrialisation and the Asian Economy. London: Routledge

Impey, Oliver, Jorg, Christiaan J.A. and Mason, Charles. 2009. Dragons, Tigers and Bamboo: Japanese Porcelain and Its Impact in Europe – The Macdonald Collection. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre

Impey, Oliver. 1984. ‘Japanese Export Art of the Edo Period and its Influence on European Art’, Modern Asian Studies. 18, 4: 685-97

Jorg, Christiaan J.A. 2003. Fine and Curious: Japanese Export Porcelain in Dutch Collections Hotei: Amsterdam

Nogami, Takenori. 2017. ‘The Trade Networks of Japanese Porcelain in the Asia-Pacific Region’ in Berrocal and Tang (eds.) Historical Archaeology of Early Modern Colonialism in Asia Pacific. Gainesville: University Press of Florida

Prakash, Om. 1999. ‘The Portuguese and the Dutch in Asian Maritime Trade: A Comparative Analysis’ in Chaudhury and Morineau (eds.) Merchants, Companies and Trade: Europe and Asia in the Early Modern Era. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Schottenhammer, Angela (ed.). 2008. The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verla

Screech, Timon. 2002. The Lens Within The Heart: The Western Scientific Gaze and Popular Imagery in Later Edo Japan. Oxon: Curzon Press, Routledge

Volker, T. 1954. Porcelain and the Dutch East India Company: As recorded in the D Agh-Registers of Batavia Castle, Those of Hirado and Deshima and Other Contemporary Papers 1602-1682. Leiden: Brill

Useful Link: