Identifying a ‘rise’ in the production of punch’ǒng presents two main issues. Firstly, that of classification. Introduced by Ko Yu-sǒp in the early twentieth century, the term bunjang hoecheong sagi literally translates as ‘grey-green stoneware ceramics covered in white powder’, and attempts to classify a category distinct from other Korean ceramics of the late Koryǒ and early Chosǒn (Lee 2008: note 35). However, taken literally, Ko’s term could also easily refer to some slip-inlaid celadons of the late Koryǒ, and the close relationship between punch’ǒng and the celadon tradition from which it developed has complicated identification of the ‘start’ of punch’ǒng production. Secondly, the imposition of an art historical ‘rise and fall’ narrative onto the production of any ceramic is sometimes insufficient, as the production and consumption of wares are usually part of an ongoing transmission of styles and techniques across categories and mediums, and rarely, if ever, develop in isolation. Despite these challenges, by looking at extant examples, archaeological evidence and contemporary sources, it is possible to gain a better understanding of why particular types of ceramics became more popular at one time over another. In an attempt to situate punch’ǒng wares, this essay will look at possible reasons for the ‘rise’ in their production at the beginning of the Chosǒn in terms of the political and economic situation of that time, the characteristics of punch’ǒng itself and aesthetic and cultural trends within Chosǒn society.

![Figure 1: Punch’ǒng bottle with willow slip sanggam inlay, Chosǒn c.1400-1500, stoneware, height 30.9cm. V&A [FE.1-1981]](/media/images/korean1.width-256.jpg)

![Figure 2: Celadon kundika with willow sanggam inlay, Koryǒ c.1200-1250, stoneware, height 34.3cm. V&A [C.743-1909]](/media/images/korean2.width-256.jpg)

Celadons had been produced in Korea for centuries before the recession of the Koryǒ dynasty led to a decrease in quality and the virtual cessation of their production. Archaeological evidence indicates that punch’ǒng arose from this tradition: punch’ǒng wares were often made at the kiln sites which had previously fired celadons, and essentially used the same raw materials (one notable difference being the lower levels of iron in punch’ǒng glazes, lessening the ‘green’ effect) (Lee 2008. 40). Some decorative features of the previous tradition were also transmitted: notably the use of sanggam inlay design, the ‘most outstanding decorative feature of Koryǒ ceramics,’ which had originally been used in metal and lacquerware, but came to be applied in ceramics during the 12th century (Sohyun 2017: 124) [see Figs.1&2]. The distinguishing features of punch’ǒng were the use of slip, sometimes extensive, and the free and exuberant style of both its form and decoration. Kiln sites suggest that punch’ǒng was widely produced in the central and southern parts of the peninsula at the start of the Chosǒn; this is further corroborated by contemporary documents including the survey Sejong sillok jirji (written 1424-32), which counts 185 kilns dedicated to the production of stoneware out of 324 at the time of writing (in Seung-Chang 2011: 18).

![Figure 3: Punch’ǒng bo with underglaze iron decoration, early Chosǒn, stoneware, height: 9.2cm. National Museum of Korea, Seoul [Bongwan 10480]](/media/images/korean3.width-256.jpg)

To better understand the possible reasons behind this increase in production, it is first necessary to consider the political situation in Korea at the turn of the period and how wider factors impacted the production and consumption of ceramics. A tributary relationship between China and Korea had existed on and off and in various forms since the seventh century; a system according to which ‘vassal states periodically sent embassies to pay tribute to the Chinese emperor with goods produced in their own countries’ (Wang 2011: 146). In this way the Koryǒ and Chosǒn kingdoms ‘bought security and autonomy by forestalling Chinese intervention’ (Wang 2011: 273). However, at the beginning of the Chosǒn period, precious metal shortages related to the mining of ores and also to the increased demand for metal wares to be used in the newly enforced Confucian rituals, meant that there were not resources enough to fulfil the required tribute to Ming China (Seung-Chang 2011: 8). The ‘general shortage of precious metal’ (Gerritsen 2020: 127) resulted in royal measures to limit its consumption: a decree outlined in the Taejong sillok ordered that ‘instead of metalware, every person in the nation must use ceramics or lacquerware’ (in Seung-Chang 2011) . Such restrictions necessitated an increase in the production and use of ceramics in place of metal objects for use in both ritual and domestic environments. Shapes typical of Chinese bronzes were directly transmitted into ceramic medium, with punch’ǒng examples including this bo, [Fig.3], an ancient form used as ‘a container for rice and sorghum’ which was ‘placed at the centre of the ritual table’ and whose square body ‘symbolised the ancient belief that the world was square’ (Horlyck 2017: 20).

![Figure 4: Ritual vessel with cover, 13th century, bronze, height 16.8cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [1977.449.1a, b]](/media/images/korean4.width-256.jpg)

![Figure 5: Punch’ǒng lidded bowl with stamped design, Chosǒn, stoneware, height 18.8cm. National Museum of Korea, Seoul [Jeung 8107]](/media/images/korean5.width-256.jpg)

Yet it would be reductive to regard punch’ǒng ware merely as a metal substitute, and its divergence from standard archaistic models suggests that it held its own independent appeal in addition to its function as a practical alternative in material terms. For example, although the Chosǒn lidded bowl [Fig.5] clearly shares similarities of shape and design with the older bronze ritual vessel [Fig.4], an intricate stamped motif characteristic of punch’ǒng has been employed all over the stoneware body. The Confucian ideology behind the rituals for which such objects would have been used emphasised the importance of the present moment, the actions of daily life and an appreciation of the imperfect and ‘authentic’ which provided a link between the human and the heavenly (Yao 2000: 47).

![Figure 6: Punch’ǒng bottle vase with incised fish design, Chosǒn, stoneware, height: 29.3cm. National Museum of Korea, Seoul [Dongwon 266]](/media/images/korean6.width-256.jpg)

It is clear to see how such ideology was reflected in the spontaneity of design and technique of punch’ǒng wares, with their embodiment of ‘delight […] in the here and now’ (Koehler 2012: 39-40). The decorative appeal of punch’ǒng was not limited to ritual settings, and recognisable and familiar motifs such as common fish appear to have been widely used in the decoration of tableware. The use of this motif on wine bottles [Fig.6] was perhaps particularly appropriate, as 有魚 (I have a fish) is homophonous with 有余 (there is enough, and spare) (Levenson 1991).

The ‘carefree’ aesthetic of punch’ǒng extends to its technical features, with the diversity of decorative techniques representing a freedom and variety. Several distinctive techniques emerged, all using white slip: sanggam inlay; stamping (inhwa); incision or carving; sgraffito (johwa), where a design is carved into a layer of white slip [Fig.7]; underglaze iron (cheolwha), where iron oxide pigment was painted directly onto the surface, slip-brushing and slip-dipping (Lee 2008: 40).

![Figure 7: Punch’ǒng ‘turtle’ bottle with sgraffito peony design and underglaze iron brown, Chosǒn, early 15thc. stoneware, height: 9.4cm. National Museum of Korea, Seoul [Deoksu 6231]](/media/images/korean7.width-256.jpg)

Another key feature of these ceramics was the location of their production: these wares were made in artisan kilns rather than in government-controlled sites as celadons had been previously and as porcelain would come to be later in the Chosǒn. Punch’ǒng wares were supplied to the court and government bureaus as a form of tribute from the provinces, and their use in elite settings at the start of the period is evidenced by the stamping of specific office names on them in an attempt by the government to reduce instances of theft [Fig.8] (Seung-Chang 2011: 12). This system meant that supervisors from the Saongbang (the office responsible for royal meals and court banquets) were occasionally sent to oversee the production of particularly superior products destined for use at court (Seung-Chang 2011: 16).

This of course resulted in a certain standard of quality, but as punch’ǒng continued to be largely produced in a local rather than a centralised environment, a consequent lack of standardisation lead to regional diversity and an appeal to a localised consumer market. For example, decoration using iron oxide pigment was particularly popular at the kilns in Hakbong-ri in the Gonju area in the early Chosǒn (Minah 2017: 61). This spirit of experimentation and diversity is perhaps also reflective of the wider preoccupations of the early Chosǒn; a period of ‘self-transfiguration’ with momentous changes at every level of society, and whose very name referred to ‘dynastic freshness’ (Koh 1969: 151; Horlyck 2017: 15).

Consideration of the ‘decline’ of punch’ǒng is of use in determining the reasons for its initial ‘rise’, as details of the shifting priorities and preferences of Chosǒn ceramic consumers can bring to light those aspects of the ware which initially held appeal. The Japanese invasions of the 1590s have been identified as an ‘end’ point in pottery production (Smith 1998: 80), but contemporary records indicate that by this point stoneware kilns producing punch’ǒng had already been in decline for some time; a trend connected in turn with a growing preference for porcelain and the establishment of official kilns at Bunwon in the mid-1460s.

![Figure 9: Ritual cup with ear handles, Chosǒn, 15thc., white porcelain, diameter: 11.4cm., Metropolitan Museum of Art [17.175.1]](/media/images/korean9.width-256.jpg)

Punch’ǒng’s shift in popularity had much to do with the dedication of the early Chosǒn Kings to supressing the millennium-long dominance of Buddhism in favour of the political ideology of Confucianism; a change which had a dramatic and sustained effect on material culture at many levels, including ceramic production. One of the key roles of a monarch in Confucian terms was to ‘set the standard for dignified and righteous behaviour as taught in the Confucian classics’ (Lee 2008: 22), and so by adopting white porcelains as the official ware of the court, King Sejong established the close association of these wares with model Confucian practice. Aesthetic features were aligned with Confucian ideology: for example, the concept of Gyeongbok, ‘bright happiness’, which was a term from one of the Five Classics of Confucianism and provided the name for the palace in the newly created capital (Horlyck 2017: 18), was encapsulated in the translucent brightness of porcelain bodies.

As an elite product, desire for porcelain grew among the Yangban officials and scholars of the early Chosǒn. Although these elites were consumers of stamped punch’ǒng (and were largely responsible for a ‘flowering’ of refined examples of punch’ǒng in the mid-15th century), they made no secret of their admiration for porcelain and its ‘combination of spontaneity and simplicity’ (Seung-Chang 2011: 18-20). These features were also characteristic of punch’ǒng: how, then, did the two wares differ in terms of reception, significance and consequent appeal to Confucian elites? Although the free-spirited and innovative nature of punch’ǒng reflected the momentous changes at the start of the Chosǒn period, it is also important to acknowledge that in technical, visual and perhaps connotative terms, it was also a continuation of previous celadon traditions. With its green glaze and use of slip inlay, punch’ǒng was deeply rooted in the ‘Koryǒ-Buddhism-Celadon relationship’ which the new government was committed to replacing with the ‘Chosǒn-Confucianism-White Porcelain’ alternative (Kim 2002: 12-13). Use of wares that were rooted in Goryeo tradition, was therefore not desirable, and a new form of practical ceramic was required (Kwon 2014). Additionally, porcelain was regarded as a ‘luxury’ product and was smuggled into Korea from China before the establishment of the Bunwon kilns. The rise in desirability and exclusivity of white porcelain represents a shift away from consumption of locally-produced regional wares, which had previously been enjoyed and even prized as objects of novelty (Namwon 2017: 12), reflecting the ‘gradually commercialising’ society of the period (Ebrey & Walthall 2014: 257).

Thus, the emergence of white porcelain as a ware characterised by its status as both luxury product of centralised, government kilns and embodiment of Confucian ideology emphasises the significance of punch’ǒng as its counterpart: a locally produced ware with many regional variations, often made in re-purposed celadon kilns and connected deeply to the ceramic traditions of the previous period. While this came to be displaced in later production and consumption practices, in the initial ‘transitionary’ phase of the Chosǒn, Punch’ǒng seems to have held appeal as a regional and varied product which simultaneously embodied an unrestrained, innovative spirit and a strong link to previous practices.

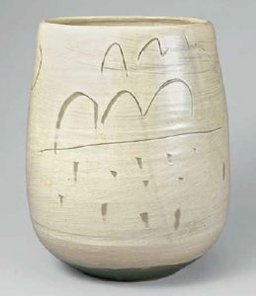

Care must be taken in the attribution of the ‘rise’ and ‘fall’ of any particular aspect of historical material culture. Although it is generally accepted that that both quality and quantity of punch’ǒng declined in the period following the establishment of the official kilns and Japanese invasion, it then conversely saw a period of great impact and appreciation in Japan. Growing awareness and appreciation of punch’ǒng in the West is demonstrated by its first exclusive exhibition outside Asia at the Metropolitan Museum in 2011-2012, and its production is enjoying a new ‘rise’ at the hands of contemporary Japanese and Korean artists such as Yoon Kwang-cho [Fig.10]. The task facing art historians thus widens: although the consideration of a singular and historic increase of production is necessary, wider understanding of punch’ǒng requires analysis of a fluctuating and ongoing narrative which continues to have an impact in Korea and beyond.

Bibliography

Ebrey, Patricia & Walthall, Anne. 2014. East Asia: A Cultural, Social and Political History. Boston, MA: Cengage

Gerritsen, Anne. 2020. The City of Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain and the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

Horlyck, Charlotte. 2017. ‘Arts and Culture in the Confucian State of Chosǒn’ in Richard Linger (ed.) Chosǒn Korea: Court Treasures and City Life. Singapore: Asian Civilizations Museum

Kim, Jaeyeol. 2002. Handbook of Korean Art: White Porcelain and Punch’ǒng Ware. Seoul: Lawrence King

Koehler, Robert. 2012. Korean Ceramics: The Beauty of Natural Forms. Seoul: Seoul Selection

Koh, Sung Jae. 1969. ‘The Place of the Pottery and Porcelain Industry in East Asian History’ Journal of Korean Studies. 1:1 July-December 1969

Lee, Soyoung. 2008. ‘Art and Patronage in the Early Chosǒn’ in Lee (ed.) Art of the Korean Renaissance, 1400-1600. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Levenson, Jay A. (ed.). 1991. Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration. New Haven & London: National Gallery of Art

Minah, Woo. 2017. ‘Changes in the Characteristics of White Porcelain Decorated with Underglaze Iron-Brown Produced in Chosǒn Official Kilns’ in Journal of Korean Art and Archaeology. 11:59-78

Namwon, Jang. 2017. ‘Treasured Ceramics of the Late Joseon Period Viewed from a Material Culture Perspective’ in Journal of Korean Art and Archaeology. 11:11-27

Seung-Chang, Jeon. 2011. ‘Buncheong: Unconventional Beauty’ in Lee &

Seung-Chang (eds.) Korean Buncheong Ceramics from the Leeum Samsung Museum of Art. New Haven & London: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Smith, Judith G. (ed.). 1998. Arts of Korea. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Sohyun, Kwon. 2017. ‘A Study of White Porcelain Cup and Stand’ in Journal of Korean Art and Archaeology. 11:124-134

Sohyun, Kwon. 2014. ‘Ceramics and Ritual Vessels of the Royal Household’ in Treasures from Korea: Arts and Culture of the Chosǒn Dynasty, 1392-1910. New Haven: Yale University Press

Taejong sillok vol. 1, 384:a (vol. 13, 1st month, 19th day of the 7th year [1407]), quoted in Lee & Seung-Cheng (eds.). 2011. Korean Buncheong Ceramics from the Leeum Samsung Museum of Art. New Haven & London: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Wang, Yuan-kang. 2011. Harmony and War: Confucian Culture and Chinese Power Politics. Columbia: Columbia University Press

Yao, Xinzhong. 2000. An Introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press