Antique Japanese Porcelain

The earliest Japanese ceramics made in Japan date back to the Neolithic period but porcelain production began in Japan several centuries after it was first made in China in the Tang period (618-960 AD). Prior to the more refined porcelain produced at the five main kilns in Japan, home produced ceramics could not compete with the refined expensive Chinese porcelain imports. It should be noted that even from early times there were a great many kilns in Japan.

Antique Japanese porcelain tends to be underestimated since it is identified with the comparatively plentiful Imari porcelain (a term used in the West), which although has merit does not match up to the best Chinese porcelain. Kakiemon porcelain, unlike Nabishima, was exported to the West where it was held in such high esteem that it was copied by numeorus 18th century European factories including Meissen, St Cloud, Chelsea and Bow. Early Ko-Kutani is extremely rare and sometimes quite difficult to differentiate from those pieces produced in the 19th century which can also be quite well potted and highly iridescent. Hirado also produced some very attractive porcelain in the second half of the 18th century.

Nabeshima Porcelain

It was the two invasions of Korea in the 1590s led by Toyatomi Hideyoshi that enabled the accompanying feudal lords to bring Korean potters to Japan. Lord Nabeshima took back some of these Korean potters to his southern island home of Kyushi in the Hizen province. Some of the best artists were employed at the Arita kiln. Production at the Arita kiln was later moved to Minamikawara to avoid the secrets of porcelain production being leaked. Subsequently, the Nabeshima clan moved to Okawachiyama. Fine porcelain now referred to as Nabeshima was made for the Emperior and Shogan around 1700, using such artists as Kaiemon, Genemon and Hatase Jūbei.

Japanese porcelain production by the Nabeshima clan and elsewhere was initially not very fine. At first mainly Karatsu ware was produced. It was only during the Enpou era (1673-1681) and the following twenty five years or so that best Nabeshima porcelain was produced. The inspiration for the surprisingly modern looking designs came primarily from plants and kimono patterns. In addition to under-glaze blue, the four colours used were red, blue, green and yellow. The finely decorated dishes have well balanced shapes and early examples were made to exact dimensions. The porcelain is very refined and the early polychrome wares have what is referred to as the cloisonné effect; faint outlines that define the decorative motifs. This porcelain has been so highly prized that it was often kept in specially made boxes and consequently sometimes there is little sign of wear. After about 1710 Nabeshima began to deteriorate in quality.

Kakiemon Porcelain

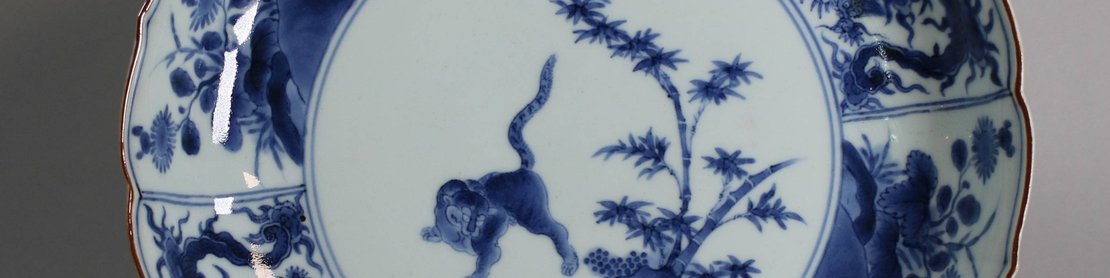

The antique Japanese Kakiemon kilns also benefited from Korean expertise. Unlike Nabeshima, Kakiemon designs were sometimes influenced by what the Dutch traders thought would appeal to the European market. These designs proved to be a great commercial success judging by the numerous examples to be found in European palaces and the grand country houses of the European nobility. As already mentioned, one consequence of their success was that the designs were copied by most of the important 18th century European porcelain factories. There is often confusion as to what makes polychrome Japanese porcelain Kakiemon. One distinguishing characteristic is the blue enamel similar to that used in China during the Kangxi period (1662-1722). Dishes were fired on stilts and the marks are just about visible. The most appealing Kakiemon porcelain is decorated in under-glaze blue with often ephemeral scenes that hint rather than portray real-life scenes.

Hirado Porcelain

Collections of antique Japanese porcelain like the Kurtzman Family Collection contains many later examples of Hirado porcelain but the earlier wares from the 17th century and early 18th century are few and far between. The earlier wares tend to have a less lustrous, duller, thicker glaze (which sometimes contains faults) with a faint greenish tinge. Another characteristic is that foot rims are generally thicker and the fired iron content tinges them red. The paste has a compact look to it very much like that seen on Chinese Kangxi porcelain. The drawing on the earlier pieces tends to be bolder whereas the drawing on later porcelain has a tendency to be more delicate and detailed. The spacing of the decoration is often not so good and ill suited to the shape it is being applied to. Consequently, many late pieces have a mechanical and sterile quality.

The antique Japanese sake flask illustrated here is a shape that is often associated with late 19th century Hirado porcelain but this example dates from the second half of the 18th century.

Museums for Japanese Porcelain

Recommended Reading

Cleveland, Richard S. 200 Years of Japanese Porcelain. Pub. City Art Museum Saint Louis.

Impey, Oliver. Japanese Export Porcelain – catalogue of the collection of the Ashmolean Museum Oxford. Pub. Hotei Publishing . Mr Impey is one of the few Westerners to have gone out to the kilns in Japan and return with a collection of shards which are now at the Ashmolean.

Impey, Oliver. The Early Porcelain Kilns of Japan: Arita in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

Lawrence, Louis. Hirado: Prince of Porcelain. Art Media Resources, Ltd., 1997.

Les Cadeaux Au Shogan Porcelaine Prechieuse des Seigneurs de Nabeshima from the Espace des Arts Mitsukoshi Etoil. This is a very well-illustrated catalogue which gives precise sizes to which Japanese Nabeshima dishes were made.

Shimura, Goro. The Story of Imari: The Symbols and Mysteries of Antique Japanese Porcelain. Berkeley, Calif.: Ten Speed Press, 2008.

Wilson, Richard L. Inside Japanese Ceramics: A Primer of Materials, Techniques, and Traditions. New York: Weatherhill, 1995.