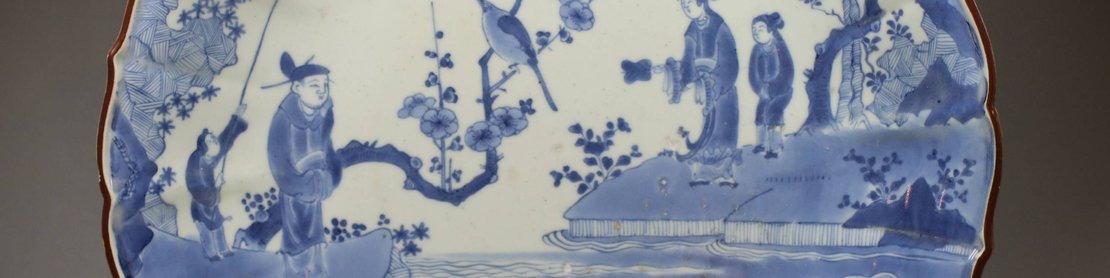

The Dutch East India Company, or VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compangnie) was founded at the beginning of the 17th century and very early on began to trade in Chinese ceramics as a profitable commodity, both within Asia and in North Western Europe. When the Chinese trade began to decrease in the 1640s, due to a civil war in that country, the Company substituted Japanese wares to meet the ever-growing demand for Oriental ceramics. By the 1660s there was a healthy trade in Japanese ceramics to the Netherlands. During the 1680s the new Chinese emperor Kangxi (1662-1722) resettled internal order and the Chinese potters were again gainfully employed, Japanese production therefore declined sharply after 1730. The aesthetic effect of Japanese porcelain upon European production is easily overshadowed by the influence of Chinese porcelain. Japanese decoration is generally formed through blocks of colour; this style is in strong contrast to Chinese porcelain which spreads to fill the whole space. Chinese designs are more fluid. Chinese porcelain was also cheaper and more plentiful to buy in mainland Europe. The Japanese shared common motifs with the Chinese such as flowering branches, and ‘scholar’ figures, as seen on this blue and white dish (Fig. 1), scrolling lotus leaves common in Chinese decoration in Japanese ceramics are the distinctive karakusa pattern. In emulation of the Chinese, blue and white wares made for export often had a square mark at the base, such as the fuku mark seen here (Fig. 2).

However, the eighteenth century European ceramic factories owe a great debt to Japanese wares. A comparison between Kakiemon pieces (Fig. 3) and those produced by the Meissen and Chantilly factories in Germany and France will prove this (Fig. 4), as well as the English examples produced by the Bow, Chelsea and Worcester factories in the latter part of the eighteenth century with Japanese Imari wares. While Japanese porcelain has been somewhat overlooked by modern collectors in the West, recent scholarship is readdressing this imbalance; such as Porcelain for Palaces: The Fashion for Japan in Europe 1650-1750, an excellent exhibition held at the British Museum in 1990. The accompanying catalogue demonstrated in particular the crossover between the English factories with Japanese and Chinese wares. This exhibition also displayed a dish of near identical design to Figure 1, no. 133, formerly in the collection of the Duchess of Portland (1715-1785). Christiaan Jörg’s, ‘Fine and Curious, Japanese Export Porcelain in Dutch Collections’, also illustrates a dish of this design (no.162., p. 147, published 2003).

Another Japanese dish from the collection of the Duchess of Portland has made its way to the Ashmolean Museum (Accession number EA1978.716) and is similar to Figure 5, like the example in Figure 1 it has a lobed rim with an iron-brown glaze in contrast to the fine blue and white enamelling. This design was copied by the Dutch potters. While the one example is a complete picture and the other contrasting the central decoration with the outer border, both show the confidence of the Japanese design managing to harmoniously combine ‘active’ narrative elements such as the motion of water, gesturing figures, creatures and flowering branches and yet creating a controlled and balanced sensation of stillness and timelessness. Neither are over-decorated, imagine the top half of Figure 5 with more blue decorated elements in the sky and the result would feel overcrowded and draw attention away from the focal figures in the central triangle, while the bottom blue water part would feel too heavy. As it is, the flowering prunus branch and curling pine tree bridge the divide between the sky and the central action, while also mirroring the sense of the near cliff and the far river bank. This is done without recourse to perspective as a western painter would use, and without a clear painterly foreground and background. Similarly, try to imagine the first lobed dish with a more crowded central roundel, your vision would be distracted from the two figures whose gaze leads you at once to the waterfall on the opposite bank, but also to the two crawling tigers of the border, the one on the left whose gaze and outstretched paw is clearly indicating back towards these two figures. The pacing action of the top half is balanced by the asymmetrical rockwork and blossoming branches of the bottom half of the border.

It is therefore difficult to exactly locate pieces to one kiln or one workshop, although easy to see that the late seventeenth century wares are the best for their variety, clarity of design and simple aesthetic brilliance. The more time spent in the company of these fine pieces, the richer the observer.

Museum Links For Japanese Porcelain

For further reading see:

Japanese Porcelain, Soame Jenyns, London, Faber & Faber, 1965, First Edition. Republished 1979, ISBN 0 571 06446 9

Nabeshima ‘Porcelain for the Shogunate’’, the Kyushu Ceramic Museum

Les Cadeaux au Shogun: porcelaine precieuse des seigneurs de Nabeshima

China Institute Gallery: Celebrating 40 Years of Excellence: 1966-2006, from the exhibitition Trade, Taste and Transformation: Jingdezhen Porcelain for Japan, 1620-1645, 2005, ISBN-10: 0-9774054-0-0

Kakiemon: The whole Aspect of Kakiemon Style – special exhibition 1999, The Kyusu Ceramic Musuem, 2002 Hotei Publishing and Oliver Impey, the Ashmolean Musuem, Oxford, ISBN 90-74822-16-9

Dragons, Tigers and Bamboo: Japanese Porcelain and Its Impact in Europe; The MacDonald Collection, the Gardiner Museum of Ceramic Art, Douglas & McIntyre 2009 Oliver Impey, Christiaan Jorg, Charles Mason, ISBN-10: 155365434X ISBN-13: 978-1553654346